The Process of Determining Representative Districts

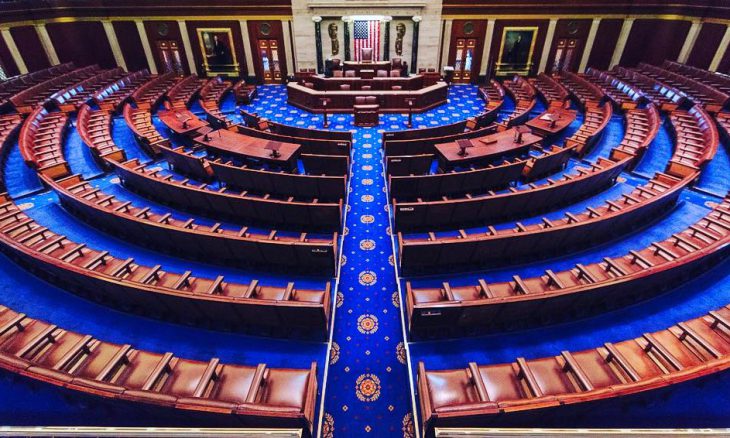

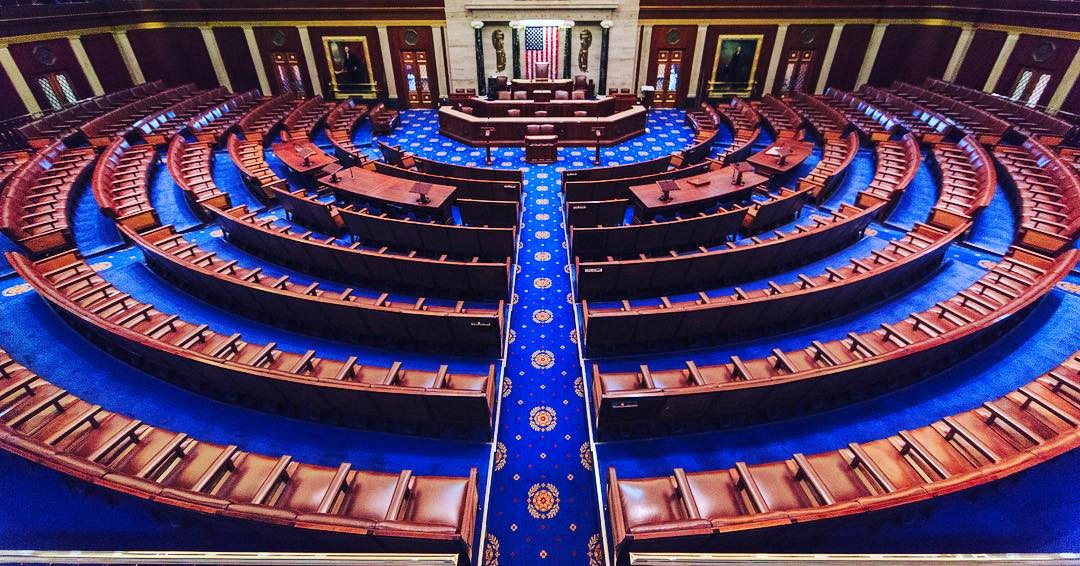

Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution tells states how to choose the number of legislators that will represent them in the House of Representatives. Although the Framers did not use the word “district” when they outlined how Congressional representatives would be chosen, today the redistricting process has become that means.

Beginning three years after the first meeting of the Congress of the United States, and every subsequent ten years when a census is taken, the number of representatives is chosen based on the census enumeration. Each state must have at least one representative, and the number of representatives shall not exceed one for every 30,000 people.

In the 1960s, the Supreme Court decided that there be a rule of population equality for congressional and other districts and how those districts are drawn, but Congress has passed various apportionment statutes over time that have required single-member districts and the one that currently exists is about 90 years old.

Based on the 2020 Census, Texas was awarded an additional two seats. The states of Colorado, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon were each awarded one new seat in the House of Representatives. California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia east lost a single seat.

States that either added or lost a seat were required to redistrict to provide representation across the state maps. However, as populations shift within states, even those states without a gain or loss will often redistrict. All 50 states have finalized their congressional map for use in the November election, a major checkpoint in the once-a-decade process.

In most states, the state legislature is responsible for drawing district lines. However, 15 states use special redistricting committees to draw state legislative districts. Six of those states also use a board or commission to draw congressional plans, while ten states use an advisory or remedial commission in the event the legislature is unable to pass new plans. The Justice Department and independent groups can be helpful to ensure that redistricting is fair and provides effective representation for all.

Of course, since the bodies drawing the redistricting lines are political in nature, boundaries may be drawn with the intention of influencing who gets elected—a process known as gerrymandering.

In the redistricting cycle for this year’s midterm elections, it is the first time that a Supreme Court 2019 ruling on gerrymandering will be employed. In Rubio v. Common Cause, the Court ruled 5-4 that partisan redistricting is a political question, not reviewable by federal courts and that those courts cannot judge if extreme gerrymandering violates the Constitution. The ruling put the onus on the legislative branch, and on individual states, to police redistricting efforts.

“We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote for the majority. “Federal judges have no license to reallocate political power between the two major political parties, with no plausible grant of authority in the Constitution, and no legal standards to limit and direct their decisions.”

Chief Justice Roberts noted that excessive partisanship in the drawing of districts does lead to results that “reasonably seem unjust,” but he said that does not mean it is the Court’s responsibility to find a solution.

When the current redistricting cycle began, there were some states which determined to reform the district drawing process. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, in the end, results were mixed. Their analysis states, “If reforms removed politicians from the line-drawing process, they worked. By contrast, if politicians were left in the mix, reforms broke down.”

As of October 12, 2022, a total of 72 cases had been filed challenging congressional and legislative maps in 26 states alleging racial discrimination and/or partisan gerrymanders. Forty-two remain pending at either the trial or appellate levels.

Even though cases may be pending, in trial, or on appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court has allowed states to use the allegedly “unlawfully” gerrymandered congressional maps in the 2022 midterms. Their ruling will guide federal judges considering cases around the country. The decision will also affect who gets elected to the House of Representatives and may determine the control of Congress. While it may not change which party has control in Congress, it could affect the size of the majority of that party.

God calls His people to act justly in all things. “He walks righteously and speaks uprightly, who despises the gain of oppressors, who shakes his hands, lest they took a bribe, who stops his ears from hearing of bloodshed and his eyes from looking on evil, he will dwell on the heights, his pace of defense will be the fortress of rocks” (Isaiah 33:15-16). The apostle James wrote, “If you really fulfill the royal law according to the Scripture, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself,’ you are doing well. But if you show partiality, you are committing a sin and are convicted by the law as transgressors” (James 2:8-9).

How then should we pray?

- For the members of state legislatures as they determine the political and ideological course of their states.

- That the justices of the Supreme Court would continue to provide the balance of power outlined in the U.S. Constitution.

- For the justices and judges who hear court cases regarding elections to be discerning in their rulings and decisions.

- For those who draw district maps to do so without bias or partiality.

- For wisdom for members of Congress as they consider whether or not redistricting reforms are necessary.